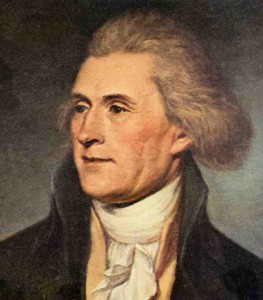

Jefferson, America’s First Wine Expert

Many people immediately associate with Thomas Jefferson and wine with the bottle of 1787 Chateau Lafite engraved with Jefferson’s initials that sold at auction (1985) for 105,000 pounds Sterling. Of course, later, the authenticity of the bottle(s) came into question in an extended investigation, but the images of the old, dusty bottles remain.

Thomas Jefferson was America’s first wine connoisseur. Jefferson approached wine as he did virtually all subjects, including architecture, science, and farming, as a passion and field of constant study.

Wine appreciation and cultivation hit a fast track when Jefferson met Philip Mazzei, an Italian merchant and viticulturist. Mazzei had met Benjamin Franklin in London in 1767 and was then tempted by the idea of developing a customer base in the New World and the possibility of moving operations to Virginia.

In 1773, Mazzei did just that, landing in Williamsburg, Virginia, where, within a day of his arrival, he met both Thomas Jefferson and George Washington. Mazzei had come to Virginia at the urging of Thomas Adams, seeking to develop vineyards in Augusta County.

Adams and Mazzei set out on the journey from Williamsburg to Augusta County and stopped over at Jefferson’s Monticello. In the early morning hours, before much of the house had risen, Jefferson took Mazzei on a tour of the lands surrounding Monticello. Jefferson showed Mazzei a nearby clearing that was for sale. Jefferson suggested that he could help negotiate the purchase of the land and offer Mazzei a sizable lot of his own uncleared land to sweeten the deal.

When the two returned to Monticello, the others were waiting. Adams greeted the pair, proclaiming to Jefferson, “I see in your eyes that you have taken him from me. I knew you would do that.”

While Mazzei expanded Jefferson’s understanding and appreciation of wine, it was certainly Jefferson’s term as United States Minister to France (1785 to 1789) that he sharpened his palate. In 1787, Jefferson embarked on an epic three-month, 1,200-mile journey through France and Northern Italy. Jefferson hit many of the wine regions that are so vital today, including Champagne, Burgundy, Beaujolais, Bordeaux, Languedoc, Loire, and Provence. In Italy, his travels were far less extensive, going no further south than Genoa.

By the time that Jefferson returned from France he had extensive knowledge of the wines of Europe and was far more experienced than any contemporary American. Many of the wines that he adored are very much in fashion today: Meursault, single vineyards in Pommard, numerous chateau in Bordeaux including Lafite and d’Yquem, Hermitage (primarily white), Spanish Sherry, sparkling Nebbiolo from Piedmont (Italy), and the Tuscan Montepulciano that he wrote, “No wine pleases me more.”

Jefferson Had a Presidential Wine Cellar

Whilst President of the United States (1801-1809), Jefferson kept an extensive cellar. In these years, he spent roughly 8% of his salary on wine. He also worked within the framework of the newly formed Republic to bring down the tariffs imposed on imported wine. Jefferson strongly believed that the health of the citizenry would be better served if wine was consumed more frequently than Port and Madeira or stronger spirits. He famously wrote, “No nation is drunken where wine is cheap…”

Jefferson advised his Secretary of the Treasury, Albert Gallatin, to rework the tariffs imposed on wine, bringing them more in line with other alcoholic beverages. He even devised a clever chart of a new tariff scheme that was too shared with Gallatin. Jefferson argued, “[T]he taste of this country [was] artificially created by our long restraint under the English government to the strong wines of Portugal and Spain.” These stronger fortified wines traveled with great ease compared to the typical table wine, which is far more delicate.

Jefferson was so enthralled by wine that all but six lines of a letter to his friend James Monroe congratulating him on winning the presidency were devoted to wine. In this correspondence, Jefferson included detailed advice on maintaining a cellar as commander in chief.

Wine and Health

While in his 30s, Jefferson was advised to drink wine for health purposes. Through the years, Jefferson became convinced of wine’s medicinal properties and advised his friends and family to consume wine for health. Later in life, in a letter that would act as an invoice for wine, Jefferson requested a cask of Lisbon Termo. He stated, “Wine from long habit has become indispensable for my health.”

Jefferson claimed, in 1818, that “in nothing have the habits of the palate more decisive influence than in our relish of wines.”

While wine was a part of everyday life for Jefferson he was rarely (if ever) intoxicated. The Jefferson wine glass, which is on display at his Monticello home as well as the Smithsonian, is capable of holding just shy of four ounces. Today’s standard wine pour is five ounces. Jefferson limited his intake of wine to three to four glasses, and most often, these portions were cut with water.

Jefferson was informed about wine etiquette while in France, but he never followed the English custom of drinking wine after a meal. He served cider and sometimes ale with the meal, saving the wine for after dessert.

Thomas Jefferson’s Vineyards

Jefferson Cultivated Grapes at Monticello

With the great assistance of Mazzei and his capable crew, Jefferson set about growing grapes, both vinifera (wine grapes from Europe) and local varietals. He wanted to discover which varieties performed best in the central Virginia soils and climate and ultimately produce America’s first great wine.

There are extensive records of the various plantings at Monticello, and all of them suggest that the experiment was at least frustrating. There was frequent replanting as varietals failed. Native grapes did thrive in selected patches but these grapes were eaten at the table. There is no credible evidence that wine was ever made at Monticello while cider, beer, and Whiskey making was an ongoing concern.

The 1807 planting of 287 rooted vines and cuttings of 24 European grape varieties was the most ambitious of seven major experiments.

The vineyards were organized into 17 narrow terraces, each reserved for specific varieties that Jefferson had received from various sources. Many of these vinifera vines had probably never been grown in the New World.

The primary cause of the failure to cultivate vinifera grapes was a tiny root louse known as phylloxera. This destructive pest would later devastate the vineyards of France in the mid- to late 19th century. The solution was to graft the European vinifera grapes onto American varietal rootstock, as the native American varieties were immune to the pest.

This fact has always caused me great angst, as I can imagine Jefferson’s great joy in creating great wines from Monticello grapes with the aid of Mazzei and others. This may have been his greatest joy, but it was never realized.

His Legacy Lives On

One of Virginia’s most prestigious AVA (American Viticultural Area) is named for Jefferson’s home, Monticello. The modern Monticello AVA was officially established in 1984 following a petition by local grape growers. The AVA is centered around Charlottesville and encompasses parts of Albemarle, Fluvanna, Greene, Orange, and Nelson counties. This picturesque appellation is nestled along the eastern slopes of the Blue Ridge Mountains; it spans over 800 square miles. Today, the Monticello AVA is home to over 40 wineries.

Jefferson’s keen dedication to growing and record-keeping lives on today. You can visit the stunning mountaintop of Monticello and the extensive grounds, including the vineyards, to see first-hand what nature offered him at Monticello.